THEY LIVED IN LEEDS

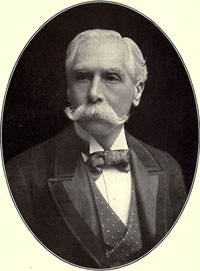

Alfred Austin (1835-1913)

Poet, Political Journalist and Critic

Leeds can boast only one poet laureate – the nation’s official poet – but in fact nobody boasts about him at all. He’s more of a shameful secret. Alfred Austin, born and brought up in Leeds, was appointed poet laureate in 1896, after four years of tussle and argument about a worthy successor to the revered Lord Tennyson and William Wordsworth. His appointment provoked a flood of criticism and insult which left his reputation in tatters and buried him for years. Search the poetry anthologies, look for a blue plaque on his birthplace: nothing. Complacent and egotistical, he lacked personal appeal, but some of his writing has charm and grace, reflecting his genuine, romantic love of English gardens and nature. Is it time to dig him up?

Leeds can boast only one poet laureate – the nation’s official poet – but in fact nobody boasts about him at all. He’s more of a shameful secret. Alfred Austin, born and brought up in Leeds, was appointed poet laureate in 1896, after four years of tussle and argument about a worthy successor to the revered Lord Tennyson and William Wordsworth. His appointment provoked a flood of criticism and insult which left his reputation in tatters and buried him for years. Search the poetry anthologies, look for a blue plaque on his birthplace: nothing. Complacent and egotistical, he lacked personal appeal, but some of his writing has charm and grace, reflecting his genuine, romantic love of English gardens and nature. Is it time to dig him up?

He was born in 1835, third of the six children of Joseph Austin, a prosperous Leeds wool merchant and magistrate, who had just had a splendid new house built on Headingley Hill - ‘Ashwood’, off North Hill Road, its gothic arched windows and tall chimneys still a feature. In later memories Alfred recalled the open fields separating it from Woodhouse Moor, where cows grazed and he used to exercise his pony – an idyllic semi-rural childhood. Poetry, especially Byron, was an early passion. His father was Catholic, so after a day school in Headingley he was sent off to the Catholic Stoneyhurst College and then to St. Mary’s, Oscott, near Birmingham, where he studied for a degree of London University, the only degree open to non-Anglicans. With vague thoughts about a profession, he entered legal chambers in London and was called to the Bar in 1857. But he was a half-hearted lawyer – he really wanted to write, and had already published a book of poetry, funded by his uncle. It sold 17 copies!

In 1860 he inherited money from this uncle, the distinguished railway engineer Joseph Locke, which freed him to write and travel. He published two books of satirical poetry, praised for their learning and elegance, and spent a long period in Italy, which he grew to love. On his return to England he continued writing, published two novels, and married the daughter of an Irish landowner, Hester Homan-Mulock. They enjoyed a year-long honeymoon in his beloved Italy, embroiled then in political turmoil.

Politics were close to his heart. A staunch, deeply patriotic Tory, he was taken on as leader-writer for the right-wing ‘Standard’ newspaper. As their correspondent he travelled to Rome in 1869 to cover the first Vatican Council and then in 1870 was at the Siege of Paris. He stood for parliament twice as a Conservative, for Taunton in 1865 and Dewsbury in 1880, egged on by Disraeli, but lost. So he focussed on political journalism, founding and editing the National Review, a platform for the Tory party. He was a close friend of Lord Salisbury, and totally in tune with his anti-reform policies.

Disliking London, he looked for a rural retreat where he could live like a traditional country squire and write. In 1867 he and Hester fell in love with the picturesque Swinford Old Manor House near Ashford in Kent and bribed their way to buying it. They spent the rest of their lives there creating their perfect garden, the inspiration for his most popular work: ‘The Garden that I Love’ (1894), and its sequels ‘In Veronica’s Garden’ and ‘Lamia’s Winter Quarters’, all running to many editions – idylls in prose, interspersed with poems and whimsical conversations on nature and life. Further volumes of lyrical poetry, poetic criticism (he harshly dismissed old favourites like Tennyson!), satires and dramas, and finally an autobiography flowed from his pen – over 40 books in all.

In 1896, after other candidates had been rejected or had refused, he was appointed Poet Laureate, on Lord Salisbury’s recommendation as Prime Minister. The press had a field day mocking his work, picking on various dud lines particularly in his later ‘official’ odes, and even poking fun at his short stature (about five feet). But he was impervious: confident, sure of his own worth and the rightness of his views on Queen, country, empire, and literature. He revisited Leeds in 1904 to receive an honorary degree from the newly created University, and gave a characteristic lecture on the ‘progressive lunacy’ of giving poor children free meals in schools. He died in 1913, on the brink of the great upheaval of the First World War.

He was included in a famous anthology of bad poetry, but the kind view is that at his best he was ‘a true but not a great poet’ – you can taste his work yourself now on the internet.

Eveleigh Bradford

March 2015